I hadn’t heard of Marty until my partner recommended it for the blog, which was a little embarrassing when I found out how well-received it was in its day. A low budget film version of a tv production, Marty won both the Palme d’Or and the Academy Award for Best Picture, and was a career highlight for star Ernest Borgnine, who until that point had been best known for his role as a villainous staff sergeant in From Here to Eternity. The trailer for The Catered Affair, Borgnine’s next film, perfectly illustrates the impact of Borgnine’s work in Marty. Borgnine isn’t the star of The Catered Affair, nor is he the most glamorous star in the cast, but the studio used him as the spokesperson based on Marty’s warm reception by audiences.

The premise of Marty is modest and relatable, set in the present-day Bronx and following 24 hours in the life of Marty Piletti (Borgnine). We are introduced to Marty behind the counter of the neighborhood butcher shop where he works. He helps two customers in a row who inquire about his little brother’s wedding, and as “what’s wrong” with Marty that he is a bachelor at 34. Everyone in Marty’s life feels entitled to comment on his lack of a wife, a status to which he feels resigned. His bachelorhood is not pathetic in and of itself, rather the pathos comes from the relationship-shaped hole in his life. He doesn’t have much else going on besides his job (though he does have ambitions of buying the shop from his boss). A conversation with his best friend Angie is largely a repetition of “What do you feel like doing tonight?” “I don’t know, what do you feel like doing?.” At Angie’s suggestion, he phones a woman he had met a month prior– “the big girl,” as Angie describes her– to ask for a date. We only see Marty’s half of the conversation, the camera slowly pushing in on his face as he is rejected (“the big girl” presumably being someone who ought to struggle with finding a date for Saturday night as well), highlighting his loneliness and vulnerability. Marty is shy and socially awkward, but he explicitly attributes his bachelorhood to his size and physical appearance. “Whatever it is that women like, I ain’t got it,” he tells his mother (Esther Minciotti) when she tries to convince him to spend his Saturday night at the dancehall where Marty’s cousin met his wife. When she persists, his facade of resignation slips to reveal a raw, frustrated pain. “I’m just a fat little man, a fat ugly man… you know what I’m gonna get for my trouble? Heartache, a big night of heartache.”

Marty and Angie go to the dance hall. Angie quickly finds someone to dance with him, but after getting a quick once-over, the woman Marty asked for a dance turns him down. As Marty is standing by himself, Clara (Betsy Blair) enters the film. Paralleling Marty’s introduction, she is at the receiving end of someone’s disapproval: her blind date is disappointed that he has to waste his Saturday night with someone as plain-looking as she. He offers Marty $5 to take Clara off his hands; Marty refuses, and watches as Clara gets ditched regardless. Marty becomes her knight in shining armor. In a subsequent scene, the camera glides through the crowded dance floor to find Marty and Clara dancing together, commiserating over their unlucky social lives and finding refuge in each other. “I’m really enjoying myself… you’re not such a dog as you think you are,” he tells her. “Maybe I’m not such a dog as I think I am,” he adds after she tells him that she’s also having a good time.

As they get to know each other over the course of the night, we see that Clara and Marty are both kind, sensitive, optimistic people. The romantic scenes in Marty are humble. They lack the glamour of Burt Lancaster and Deborah Kerr making out on the beach in From Here to Eternity, the Best Picture winner two years prior. Despite being average-looking people walking down a city street and getting coffee in a diner, the vulnerability that Clara and Marty share is more heartrending than the most exquisite locale or best-sculpted cheekbones could ever be. They admit to each other that they both cry easily, with a relief that borders on excitement in having found someone that relates to their experience. Later on, Marty tells Clara about how depressed and directionless he felt after returning home from World War II, and reveals that he thought about ending his own life. “I know,” is her gentle response that tells us everything we need to know about her own relationship with suicidal thoughts. What would be their first kiss in any other romantic movie is discontinued by Clara’s discomfort; where any other romantic lead would react with force or indifference, Marty crumbles into frustration and self-loathing. Instead, Clara expresses her affection for him through her words: “I know when you take me home I’m just going to lie in my bed and think about you.”

The pain their loneliness causes is very real, but seems to be largely due to the opinions of others. Clara is criticized for not being pretty, Marty is criticized for being bachelor. The film does not portray marriage or a family life as intrinsically providing more happiness. Marty’s mother and Aunt Katarina (Augusta Ciolli) lament the life of a widow; his cousin Tommy (Jerry Paris) and his wife Virginia (Karen Steele) squabble with each other over the wails of their newborn. Marty’s friends focus on women who are “money in the bank” and fill their free time with drinking and trashy novels. However, everyone focuses their pity on Marty, the fat “dog” who is 34 and unmarried, then ridicules him for spending the night with a woman who is too old and unattractive to be considered a worthy mate. Clara’s introduction into Marty’s life reveals that his friends and family rely on him to stay in the state they they ostensibly pity. Although these days it isn’t unusual for someone to be unmarried or even living with family in their 30s (I’m sure this is more true in New York City, considering the high cost of living), the implication for audiences of the time was that Marty is in a state of arrested development. Borgnine plays him with an openness and vulnerability that borders on childlike. I was impressed by the emotional maturity with which Mrs. Piletti was written, expecting her to be a two-dimensional Italian mama, but an early scene of her serving Marty his dinner, surrounding him with serving dishes, suggests that he is smothered by her, and that her smothering is the cause of his fatness.

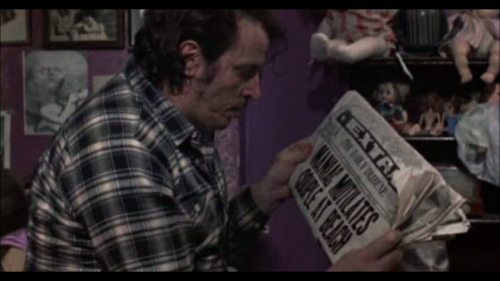

The film ends on a hopeful, but uncertain note. Initially, Marty gives in to the opinions of his friends and family, and avoids calling Clara. We see the two lovers in their respective spheres, completely miserable. Marty stands amidst a group of his friends outside their neighborhood bar, listening to the same “What do you feel like doing,” “I don’t know” conversation that has apparently reached Pinky and the Brain levels of repetitiveness. The camera slowly zooms in on him, gradually edging his friends out of the scene as they suggest going to the movies or– if my interpretation of the euphemisms of the day is correct– soliciting sex workers. Marty veritably explodes from frustration, breaking away from his friends and rushing to the payphone:

“You don’t like her, my mother don’t like her, she’s a dog and I’m a fat, ugly man! Well, all I know is I had a good time last night! I’m gonna have a good time tonight! If we have enough good times together, I’m gonna get down on my knees and I’m gonna beg that girl to marry me! If we make a party on New Year’s, I got a date for that party. You don’t like her? That’s too bad!”

Marty dials the phone. As it rings, he sarcastically picks on Angie for being a bachelor, repeating the criticisms his customers threw at him in the opening scene. Closing the phone booth door between himself and his loutish friend, we hear Marty saying, “Hello, Clara?” as the film fades to black. Contrasting with other romantic films of the day like From Here to Eternity, which ends in dramatic heartbreak for Lancaster and Kerr’s characters, the ending of Marty is modest, but that’s what makes it so special. We don’t know if Marty and Clara make a good couple in the long run, but the impact she has on him is enough for him to make two difficult choices in defiance of what he’s being told. He stands up for her worthiness despite being told that she’s a “dog,” and he stands up for his choice to pursue love with her, despite implications that as a “fat, ugly man,” he isn’t capable of finding it.